Pensions: how yours may have been affected by recent market turmoil

By Jonquil Lowe, The Open University

The early signs are that the financial markets have been appeased by the government’s October 17 decision to reverse two-thirds of its September mini-budget tax cuts.

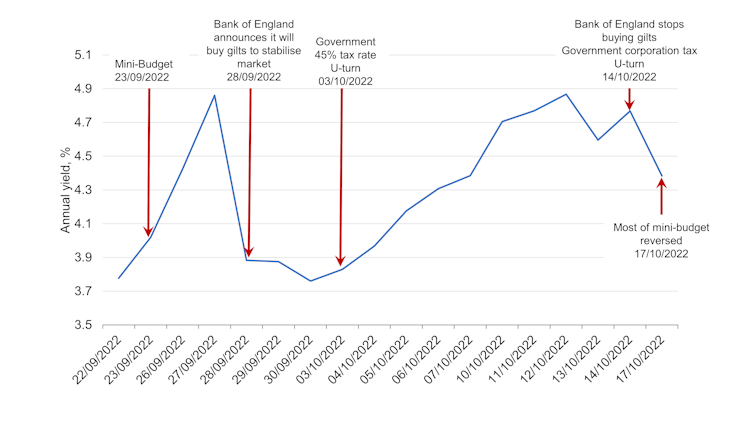

Yields on gilts – which represent long-term borrowing costs for the government and became something of a financial weather vane during the panic – saw one of the biggest daily drops on record immediately after the most recent U-turn on October 17. Yields have remained relatively low since then but are still jittery, due to uncertainty over whether the Bank of England will soon start selling gilts as a way to control inflation.

Fluctuating returns on long-term bonds

Sudden changes in the gilts market are rare, but when they do happen it can cause major problems for certain types of pension scheme, as UK pension savers have seen recently. In addition to raising borrowing costs for the government, the market mayhem following September’s mini-budget forced many pension providers to quickly cash in some of their holdings to try to weather the storm.

Whether or not this will have affected your pension depends on the type of scheme you have and how far you are from retirement.

There are two main types of pension scheme: defined contribution schemes, where you build up your own pot of savings, and defined benefit schemes, where you are promised a given amount of pension (usually a proportion of your pre-retirement pay).

The recent financial turmoil only affected defined benefit schemes offered by private sector employers, which build up a fund of investments from which to make pension payments. And even then, only the 60% or so that use specific financial strategies called liability-driven investing (LDI) to protect their holdings from the effect of falling gilt yields.

Public sector defined benefit schemes were unaffected because most are financed out of taxation and the Local Government Pension Scheme, which is a funded scheme and only uses LDI on a small scale.

So what are LDIs and why were pension schemes using this financial strategy that seem primed to wreak havoc when gilt yields rose?

Explaining the crisis

The stream of payments a defined benefit pension provider promises to its members are its “liabilities”. It holds investments (or assets) to generate the returns needed to finance these pension payments.

To work out the value of assets the provider needs to hold for a particular scheme, it must calculate the value of its liabilities. It does this by estimating the lump sum which, if invested today in long-term gilts, would produce the returns needed to pay the pensions. If the yield on gilts is low, the lump sum would be large. Conversely, if the gilt yield is high, the value of the liabilities is low.

In theory, a pension provider could meet its pension promises by actually investing in long-term gilts whose returns exactly match the amount and timing of the pensions to be paid out.

But in practice, many pension funds also invest in equities, property and other assets that are likely to produce much higher returns than gilts, but are more risky. This creates “funding gaps” when the value of these assets is lower than the value of the liabilities (the current and future pension payments). LDIs are used to protect pension schemes from the risk of funding gaps.

When a pension fund uses an LDI, it puts a small part of its assets into derivatives – financial products that can provide insurance against falling interest rates driving up the value of the scheme’s liabilities.

The pension fund must pay the LDI provider collateral to secure the product, which is typically a certain percentage of its value in cash. However, the flip side is that, if interest rates rise, pension funds have to increase the collateral they pay to the providers of these derivatives.

Interest rates usually change gradually, allowing defined benefit schemes to plan ahead to make sure they can pay extra collateral if interest rates rise, say by up to 1% a month.

However, following the mini-budget, long-term gilt yields rose from 3.8% to 4.9% in just a few days. Pension schemes were forced to sell the gilts they were holding to raise the extra cash needed to fund their collateral payments to derivative providers. This pushed up gilt yields even further, starting a vicious spiral.

As the Pensions Regulator stated at the time: “Defined benefit pension schemes are not at risk of ‘collapse’ due to rapid movements in gilt yields.”

Indeed, it’s ultimately the employers that offer these schemes to their workers who have to stand behind them. So, your pension would only be at risk if your employer became insolvent and, in that case, your pensions would still be protected (up to a limit) by the Pension Protection Fund.

The Bank of England also supported the sector by temporarily offering to buy gilts during the recent market volatility. This helped rates to fall back, but the Bank withdrew its support on October 14. This forced the government into its most recent tax cut U-turns rather than risk a resumption of turmoil in the financial markets.

Pension performance

So, despite the alarming reports that pensions were at risk, the recent market turmoil was a “liquidity crisis”. This means the problem lay with pension schemes struggling to raise short-term cash for collateral. Now gilts yields have fallen back, this crisis has eased.

Perversely, the more general situation of rising gilt yields may even have benefited some pension schemes. Rising yields reduce the value of defined benefit schemes’ liabilities, because they use these rates to calculate the value of what they will owe people when they retire.

Remember, as described above: if the gilt yield is high, the value of the liabilities is low. So, despite this short-term liquidity crisis, many pension schemes’ longer-term funding position has actually been improving.

However, the liquidity crisis has called into question whether pension schemes should be using LDI strategies. The Pensions Regulator says that LDIs have reduced the pension schemes’ risks in previous crises, such as the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

But critics argue that LDI users failed to question what would happen in extreme but plausible scenarios such as the recent spike in gilt yields. In particular, they point out that LDIs caused pension providers to have to liquidate some of their assets to meet rising collateral payments as the market fell.

Ultimately, the failure of LDIs to reduce risks as intended could further accelerate the long-established trend of employers pulling back from offering defined benefit schemes. This would be a shame since a defined benefit pension is still one of the best ways of providing for your retirement.![]()

Jonquil Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Economics and Personal Finance, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation

Spotted something? Got a story? Email: [email protected]

Latest News